5: Listen

“Deep listening is an act of surrender. We risk being changed by what we hear….Empathy is cognitive and emotional—to inhabit another person’s view of the world is to feel the world with them. But I also know that it’s okay if I don’t feel very much for them at all. I just need to feel safe enough to stay curious. The most critical part of listening is asking what is at stake for the other person. I try to understand what matters to them, not what I think matters.”

“Our goal is to understand….In understanding the cultural forces that shape such a belief, and the institutions that embolden people to act on it, we can better focus on what we need to fight: not a few bad actors, but entire policies, platforms, and echo chambers that perpetuate supremacy. In order to create a safer world for all of us, we must not only defeat such opponents but invite them into transformation.”

—Valarie Kaur, See No Stranger, Chapter 5

Understanding Listen

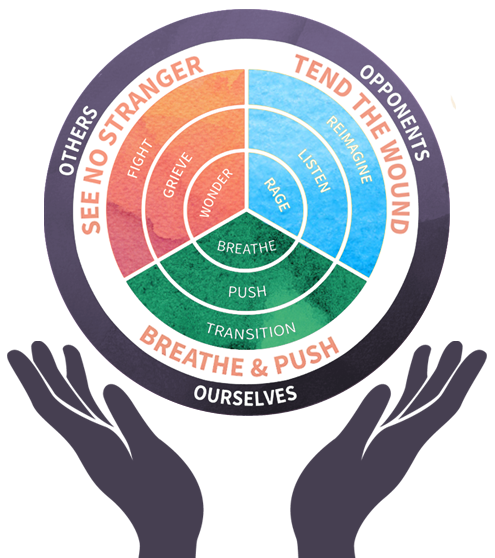

A Practice of Love for Opponents

To listen to our opponents is to seek to understand them–not to change them, or persuade them, not to compromise with them, or legitimize them. Listening to our opponents preserves their humanity—and our own.

Listening is not just a moral act; it is strategic. Listening enables us to fight in smarter ways for justice—not only to remove bad actors from power but to change the cultures that radicalize them. This is how listening to our opponents becomes a powerful act of revolutionary love.

Ask yourself: When is it my role to listen? When am I emotionally and physically safe? When can I take on the labor of listening when others are not safe to do so? We can all be one another’s accomplices.

- Think of someone you consider an opponent. Notice what is happening in your body as you see their face. If you feel activated — heart beating fast, throat closing in, any kind of constriction — that is information that this might not be the time to listen to them. This might be the time to process your own trauma, grief, and rage. So take that information in and know that there are other practices on the compass to help you with that work.

- Now think of an opponent who it is safe for you to wonder about. When you see their face, maybe you feel a little activation, but it’s not overwhelming. That is information that you might be emotionally safe. Now ask yourself, Is it physically safe for me to sit with this person and wonder about them? If yes, continue.

- Wonder about your opponent. Why do they behave that way? What is the wound that is driving them? How would they behave if they did not carry that pain or that wound, whether or not they even know it’s there? How would they behave if they were fully safe and free — at home in their bodies and at home in the world?

- What do you need to do now with your opponent? This meditation might be enough. Or you might be ready to call them. You might choose to sit with them in order to understand them. Or you might ask another to reach out to tend to them. Trust your own wisdom.

- In what ways is listening to opponents an act of revolutionary love?

- What are the goals of listening to our opponents? What is required of us when we practice deep listening?

- Who should be asked to do the labor of listening to our opponents? What are the roles of allies in the practice of listening to opponents?

- What do we risk when we listen to opponents? What might we gain? In what ways should deep listening inform our actions for justice?

- Discern when it is the right time to listen. If you are in harm’s way, if the thought of listening to your opponent grips your body with pain or panic, then it is not the right time for you to listen. Your primary responsibility is to tend to your own well-being, and build bonds with those who will labor with and for you. That is your practice of revolutionary love.

- Practice a “circle of listening.” If you are able and safe to listen, approach listening to opponents as a “circle of listening”: a dance, a process of drawing close to a person’s story, responding, returning, and drawing close again. Remember that understanding does not have to happen in one sitting. This practice is about sustained listening.

- When listening is difficult, slow down. Focus on the next breath, the sensations in your body, the ground beneath your feet. Ask yourself if you are safe. If so, release the expectation to defend yourself or your beliefs, and aim to wonder about the person you are listening to.

- Consider asking a genuine question. Remember that the goal of listening is not about granting legitimacy to someone else’s beliefs. The goal is to understand another person, and to preserve their humanity as well as our own.

- If you are able and ready to listen, you can start small. You do not need to choose your most challenging opponents to listen to. You can start by practicing wonder, building small bridges of understanding with the people closest to you, and strengthening your listening skills like a muscle, one conversation at a time.

- Practice by listening to other people listen. Podcasts like “Conversations with people who hate me” or books like Strangers in Their Own Land (Arlie Hochschild) can give us insight into the views of others without having to put ourselves directly in the role of listener.

- Be an accomplice. If you are not in harm’s way, ask yourself: Which opponents can I listen to? How can my listening to opponents ease the burden of listening from those who might be directly harmed? Focus on listening as a way to inform your actions for justice, and be open to the possibility of cultivating additional, and sometimes unlikely, allies.

- Reflect in your wisdom journal: What are you learning about how to listen? What is challenging? How do you keep returning to wonder? Remember that when we feel like we have reached our limit, wondering about our opponents returns us to love.