To Be Afraid of Hope

The new year begins in blood. Kenya is seized by violence. Benazir Bhutto is assasinated and Pakistan is consumed by riots. More soldiers are killed in Iraq. And here at home, terrible news spreads through the Sikh community — two Sikh brothers are shot to death at their restaurant in Richmond, California:

The new year begins in blood. Kenya is seized by violence. Benazir Bhutto is assasinated and Pakistan is consumed by riots. More soldiers are killed in Iraq. And here at home, terrible news spreads through the Sikh community — two Sikh brothers are shot to death at their restaurant in Richmond, California:

Two men shuffled down San Pablo Avenue on a wet December night. They passed a burger joint and doughnut shop before pausing at the door to Sahib Indian Restaurant.

One banged on the window. “You open?” he mouthed to his quarry inside.

It was a few minutes past 9 on Thursday night. Ravinder Kalsi, who owned the place with his brother, had locked up minutes earlier. Perhaps hoping to hear better, he turned the lock.

Opening the door became his last act in life.

The killers shot the 30-year-old dead in the doorway. They stepped past him and moved quickly. They touched nothing, said nothing. They found 42-year-old Paramjit Kalsi in the kitchen and shot him.

– from Inside Bay Area, Dec 28, 2007

The Kalsi brothers came to Richmond from Patiala, my mother’s hometown in India. They had run their restaurant for five years.

Over the years, I had spent time in Richmond filming interviews for Divided We Fall after other Sikh shootings. It began in June 2003 when two Sikh cab drivers Gurpreet Singh and Inderjit Singh were shot in Richmond within three days of each other. The morning after Gurpreet’s murder, his fiance in India, devastated by the news, committed suicide. Inderjit Singh was shot in the face and survived. Nothing was stolen from either cab.

Weeks later, another turbaned Sikh cab driver Davinder Singh was murdered across the bay in Redwood City. Taking into account the murder of Sukhpal Sodhi, brother of Balbir Sodhi, there were four shootings (three fatal) of turbaned Sikh cab drivers within one year in the San Francisco Bay Area alone. None of these were classified as hate crimes.

On Christmas morning 2006, Gurpartap Singh (pictured) was murdered in his cab in Richmond, California. He was a turbaned Sikh cab driver, the fifth to be shot in the San Francisco Bay Area since 2002. The police called the murder an attempted robbery; local Sikhs saw it as part of a pattern of violence against their community since 9/11. (I wrote about Gurpartap here.)

On Christmas morning 2006, Gurpartap Singh (pictured) was murdered in his cab in Richmond, California. He was a turbaned Sikh cab driver, the fifth to be shot in the San Francisco Bay Area since 2002. The police called the murder an attempted robbery; local Sikhs saw it as part of a pattern of violence against their community since 9/11. (I wrote about Gurpartap here.)

And now almost exactly one year later, two brothers have been killed in the same streets. What makes these murders different is that their killers sought them out in their restuarant without a clear motive. The FBI is now investigating the murders as hate crimes.

Driving from interview to interview in Richmond, I remember coming across stop signs riddled with bullet holes. The Kalsi brother killings pushed Richmond’s annual homicide total to 47, highest since the early 1990s.

“Something has to be done. If the police can’t capture the monsters who did this, they should just dissolve the police department and let people fend for themselves,” Gurman Bal, the brothers’ former roommate in Berkeley, told the San Francisco Chronicle. “It’s nearly like that now – lawless.”

This is how the new year begins — in blood. And I think about what the news does to us. When we hear about car bombs and coffins coming home, civil war and acts of terrorism, or the latest murders in our own community, the world feels like that — lawless — the sense that no one is controlling the situation, that no one can. It is a debilitating feeling.

And yet it is a new year. It is meant to be a time of hope. A new beginning.

How then do we listen to the bad news? Do we ignore it? become numb to it? pretend not to despair when we see the bloodstains on the ground?

As I listen to the presidential candidates speak the word ‘change’ these days, I feel the cynicism rise up from the part of my heart that is tired– the part that is afraid of hope.

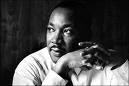

And yet hope is the only way the world has ever changed in the past. Hope is what made Martin Luther King, Jr. organize and fight and speak of his dreams. It is how women won the vote, Gandhi won a country, and my turbaned grandfather won the right to be a legal citizen of the United States.

And yet hope is the only way the world has ever changed in the past. Hope is what made Martin Luther King, Jr. organize and fight and speak of his dreams. It is how women won the vote, Gandhi won a country, and my turbaned grandfather won the right to be a legal citizen of the United States.

A bas

eless radical impossible hope that envisioned that it could be otherwise. It is the only way anything has ever gotten done. It is how I have come this far in my own healing.

Change can only happen if we first believe that it is possible.

And so somehow, I must hold onto my hope that brown faces will one day be recognized as equal Americans and live their faith without fear. I must continue to hope that our country can become a moral leader in the world, for it cannot be done without that vision. And I have to hope that what I do in response to the news, however small, counts for something.

I am afraid of hope.

And that fear is a sign for me to sharpen up all my critical thinking and — in the spirit of chardi kala — surrender to it absolutely.