Japanese American Memories

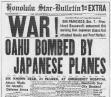

Today we sat with a group of Japanese Americans who shared their memories of the Internment during World War II. In their seventies and eighties, they exuded the warmth and wisdom of grandparents. All of them were born in the United States. The afternoon was organized by Janelle Saito, the mother my dear friend Brynn, at the United Japanese Christian Church in Clovis, California. We talked with this group for hours. At times, they drew haunting parallels to present-day America. Here are sketches of their stories.

Today we sat with a group of Japanese Americans who shared their memories of the Internment during World War II. In their seventies and eighties, they exuded the warmth and wisdom of grandparents. All of them were born in the United States. The afternoon was organized by Janelle Saito, the mother my dear friend Brynn, at the United Japanese Christian Church in Clovis, California. We talked with this group for hours. At times, they drew haunting parallels to present-day America. Here are sketches of their stories.

Aiko Ueyoka sits beside her husband Tom (pictured in the header). She is 85 years old. When the war broke, she lived in Sanger, a town in the California’s Central Valley, but when the orders for internment came, she was grouped with others in Clovis. In July 1942, she was sent to Camp #2 in Poston, Arizona, and she stayed in Barrick 22 in Block 222. “We were rounded up onto the trains like cattle.” She remembers that all they served in the barracks was mutton soup and more mutton soup. It made many people sick. To this day, she cannot stand the taste of it. It was in the camp that she met her husband Tom.

Tom Uekoya had joined the United States army before the war, but after the bombings at Pearl Harbor, the army removed all weapons from the Japanese American soldiers. They sent him to Seattle and then inland to Colorado, where they were considered to be less dangerous. On his first furlough, he visited his uncle who was interned in Poston, Arizona. This is where he met Aiko. He wrote her letters after he returned to his base. On second furlough, he visited her again, and they were married on March 18, 1944.

Aiko was now able to leave the camp and move to Denver, Colorado, where Tom was training at Camp Haley. She stayed in Denver and took care of the child of a Jewish couple, who sympathized with what was happening to her family. Tom was the only Japanese American in an all-Caucasian battalion. He was trained in #442 field artillery.

Aiko was now able to leave the camp and move to Denver, Colorado, where Tom was training at Camp Haley. She stayed in Denver and took care of the child of a Jewish couple, who sympathized with what was happening to her family. Tom was the only Japanese American in an all-Caucasian battalion. He was trained in #442 field artillery.

One day, the colonel pulled him aside. “Our battalion has been called to fight in Japan,” the colonel confided in him. “Are you willing to go?” The man shook his head, and said, “Sir, my two brothers are in Japan. I don’t want to fight against them.” The colonel sympathized with him, and sent him to Europe. When the war ended in 1945, they moved to Fresno, where they live today. Aiko remembers the discrimination they faced after the war. She wanted to become a beautician, but the beauty parlor would not hire her.

MARION MASADA

Marion Masada, now 72 years old, lived in Salinas, California. She is wearing the number she was assigned when she was sent to the camps at nine years old. “I have never forgotten this number, ” she said. Her family was forced through the Salinas Assembly Center and later to Camp #2 in Poston, Arizona. She remembers that summer as very hot. Marion confided that she was sexually abused in camp, and it took her many years to work through that trauma and regain her trust in people. After the war, her family returned to Salinas, where many soldiers had been killed in the war. But there was so much discrimination against Japanese Americans that they were not welcomed back. So her family moved to Watsonville, California. She stayed in a Buddhist temple for one month, then in a Presbyterian Church. Years later, she was married in that same church in 1955 to Reverend Saburo Masada, who then served there.

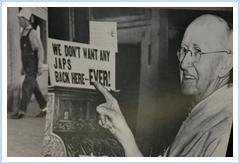

Marion brought many things to show us, including posters of the camps, a miniature of the barracks she stayed in, small crafts the Japanese American women made in camp, and photographs. One photograph shows Marion as a little girl: “I looked like an old lady!” she laughed. Another photograph shows the hateful anti-Japanese signs that were common at that time (in the picture).

Marion brought many things to show us, including posters of the camps, a miniature of the barracks she stayed in, small crafts the Japanese American women made in camp, and photographs. One photograph shows Marion as a little girl: “I looked like an old lady!” she laughed. Another photograph shows the hateful anti-Japanese signs that were common at that time (in the picture).

REV. SABURO MASADA

Reverend Saburo Masada, now 75 years old, was taken to the Fresno Assembly Center for five months before his family was forced to Jerome, Arkansas. His father caught pneumonia from the poor conditions in the barracks and was the first to die in camp. He showed us a photograph of the family gathered at the funeral, still in the barracks. In order to make room for the German POWs, they were moved once more to Rohwer, Arkanasas for one year. He returned in April 1945 to Carathers, California. His family’s farm had been watched by friends, people like my grandfather Kehar Singh who took the risk of caring for these families while they were away.

“Japanese Americans have been silent about their time in the concentration camps and have not told their grandchildren, because it was like incest. We were in love with our country and we respected authority, and suddenly our country abused us and treated us like enemies. We did not believe it for the longest time. When this happened to us, nobody was there to stand up for us. But our Sikh, Muslim, and Arab brothers and sisters are experiencing the same hate and fear, so we must speak out for them.”

“Japanese Americans have been silent about their time in the concentration camps and have not told their grandchildren, because it was like incest. We were in love with our country and we respected authority, and suddenly our country abused us and treated us like enemies. We did not believe it for the longest time. When this happened to us, nobody was there to stand up for us. But our Sikh, Muslim, and Arab brothers and sisters are experiencing the same hate and fear, so we must speak out for them.”

TOSHI SAKAI

Toshi Sakai, now 82 years old, lived in Gilroy, California. She was sent to the Salinas Assembly Center and then to Poston, Arizona. She was nineteen years old and the eldest of four sisters. Her most painful memory of the camps was remembering that her father was very sick. He was worried about how his family would survive without him, and he died in camp. Toshi had to take responsibility, since she was the eldest. After the war, Toshi met Bob Sakai in San Francisco and came to Fresno, California in 1952.

BOB SAKAI

Bob Sakai, now 83 years old, lived in Del Rey, California and was sent to Gila, Arizona from 1942-43.

When Pearl Harbor was bombed, he remembers someone pounding on his door at night. They took his father and jailed him for days on grounds of alleged misconduct at his store. His father was returned weeks later when they were already in camp. “It was like that then, the authorities abused their power in order to arrest and detain us.” Bob was twenty years old when a friend urged him to apply to college in order to get out out of the camps. He applied to Saint Paul University in Minnesota and was accepted. He later transferred to the University of Minnesota and finished at California State University, Fresno. He courted Toshi in San Francisco and they have since lived in Fresno.